For years, Urban3’s deep, customized data analyses have been used to interrogate systems of planning, design, and land use across the country. In one southern Florida county, the firm’s work was used to quite literally put these systems on trial.

Specifically, Urban3’s Joe Minicozzi was called as an expert witness on behalf of the Conservancy of Southern Florida in their case against Collier Enterprises and Collier County, which sought to develop new “villages” there. The developments – which primarily consisted of cul-de-sacs and single-family homes – were described as walkable by their designer but, as Joe described it on Urban3’s recent Lab webinar about the case: “To call this walkable is a farce.”

That is to say, no human on two legs could safely navigate a development of this design and size. Neither, for that matter, could a panther on four legs.

Among the Conservancy’s imperatives was protecting the natural habitat of the panther, an endangered species to this area of Florida, which had experienced alarming death rates due to automotive crashes and the disappearance of its natural habitat. Simply put, more people equaled fewer panthers.

Collier County adopted a progressive transfer of development rights program that was supposed to move development away from sensitive areas, and into areas already impacted; the promise was for fiscally neutral development that would be innovative and walkable, not just more conventional sprawl. One village, Rivergrass, would have required the widening of a major thoroughfare and construction of another, more than consuming the entire impact fee required by the developer and producing a deficit to the County of more than $100 million.

Source: Conservancy of Southwest Florida.

Similarly, the County’s analysis failed to take into account the long-term maintenance expenses of these infrastructure upgrades, as well as the roads internal to Rivergrass. Urban3’s analysis, which conservatively estimated four or five resurfacing cycles for the roads, indicated that an additional $40 million – $50 million of taxpayer burden was in store over the next few decades. Just looking at the capital expenses of water and wastewater pipes, and roads, the deficit could rise as high as $166M. This does not take into account costly services like police, emergency response, or sanitation.

“Rivergrass is a cautionary tale,” says Nicole from Conservancy. “It’s a warning about what happens when sprawl is allowed to happen well outside of accepted urban growth boundaries.”

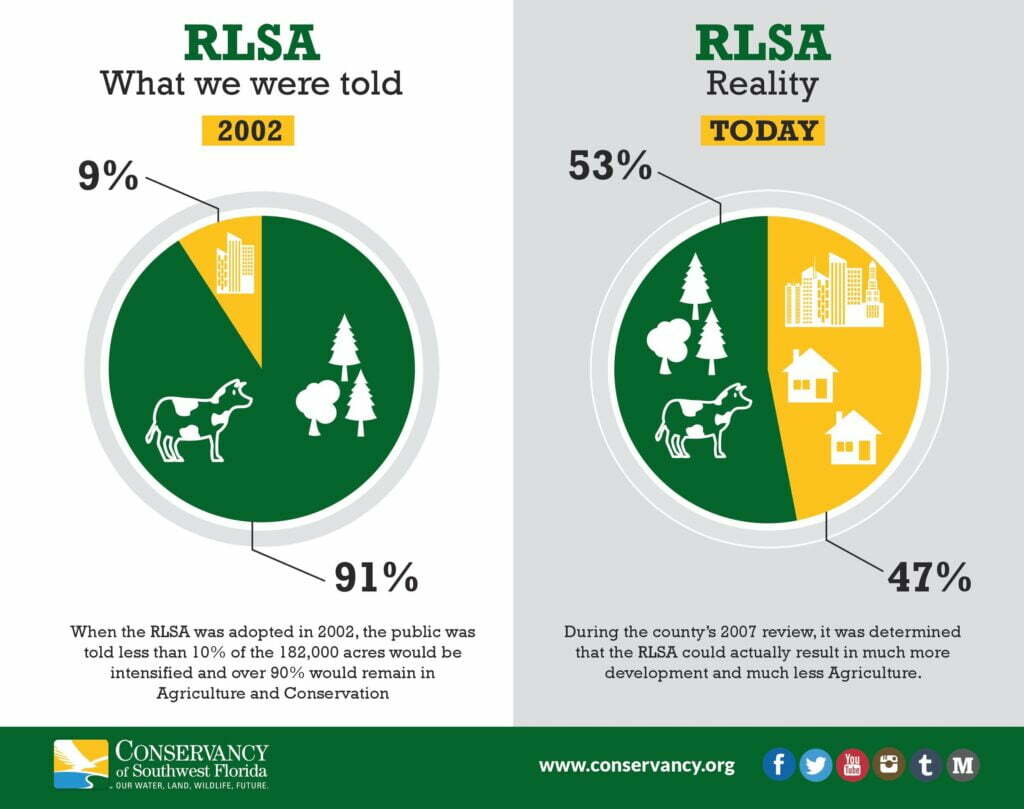

Perhaps most maddeningly, Collier County had laws on the books that were meant to mitigate exactly this kind of development. The County’s “Rural Land Stewardship Program” (RSLA) defined undeveloped, most agriculture zones within its boundaries that were meant to be protected from development. Developers could receive credits for sparing these zones and use the credits to redevelop other portions of the county. At the time of its passing in 2002, the RSLA was hailed as a visionary way to protect sensitive environmental assets in partnership with a development-hungry private sector.

Fast forward about twenty years, and it’s clear that isn’t exactly what happened. The RSLA promised to preserve 91% of the land within its boundaries for conservation and agriculture, but as of this year, almost half had been developed, most of it consumed by sprawling, costly, auto-centric uses.

Source: Conservancy of Southwest Florida.

This brings us to Rivergrass and its sprawling sister projects, Bellmar and Longwater – dozens of square miles of new development that were almost certainly going to cause irreparable harm to panthers and taxpayers alike.

Even the County’s own planning department disagreed with the proposed projects. Its final staff report, the department stated that “The Rivergrass SRA [Stewardship Receiving Area] does not fully meet the intent of the policies [of the RSLA] pertaining to innovative design, compactness, housing diversity, walkability, mix of uses, use density/intensity continuum or gradient, interconnectedness, etc. In staff’s view, the SRA is… contrary to what is intended in the RSLA” and gave it a D-minus.

Even so, the villages were recommended for approval.

The Conservancy decided to do something about it. While they could make a persuasive and cogent case for how the development would be destructive for the panthers, their legal team knew they would benefit from someone who could explain the mathematical inconsistency and incoherency of the projects in political terms – which is why Joe Minicozzi took the stand in 2021 to testify.

Joe’s testimony drew not only on an analysis of the project, but a career’s worth of understanding of how sprawl worked – who benefitted from it (developers and road builders) and who suffered (the residents who paid them.)

“Joe was an essential part of our team,” said Nicole.

Nevertheless, in court, the Conservancy’s team lost. As the Naples News put it on May 21, 2021:

The Conservancy of Southwest Florida has lost its legal challenge of a rural village known as Rivergrass. After a five-day, non-jury trial last week, Collier Circuit Judge Hugh Hayes ruled from the bench late Friday, finding in favor of Collier County and Collier Enterprises, the landowners.

One lesson is that policy isn’t perfect. Collier County had rules and regulations that were supposed to curb exactly the kind of development the Conservancy went to court to battle; they just had not been updated to reflect the changing circumstances or the reality that the data clearly proved.

Policy is also only as good as its regulators and enforcers. In this case, Collier County’s planning staff had damning things to say about a project that they ultimately recommended for approval to a body of elected officials: the Collier County Commission, none of whom were receptive to the arguments we made, no matter how factual.

We are proud of our involvement in this case because of what it represented: citizens coming together to loudly defend their values and demand better from the systems they pay into. Everywhere across the country, we need more of what we saw in Collier County, despite the discouraging result we ultimately got. Citizens deserve to see the real math on the subsidy of sprawl development. Even where there are actual impact fees that are meant to cover costs, they still fall short. Many communities collect no such fees at all.

Perhaps nobody said it better than our friend Daniel Herriges, in his terrific five-part series for Strong Towns which walked through the particulars of this case in vivid detail:

“The county’s rules may not require the use of accurate science, but panthers don’t know that. Index values mean nothing to them. They don’t get to issue bonds, pay for food on credit, collect impact fees. The Florida panther is subject to physical reality. The panthers need land they can safely traverse, and food they can eat, or they will die.”

It doesn’t have to be this way. For the most vulnerable and voiceless stakeholders in our communities, be they panthers or people, we can, and will, keep fighting.

Watch Urban3’s recent LAB video focused on the Conservancy’s approach to suburban sprawl: