Redlining is a discriminatory practice that puts services (financial and otherwise) out of reach for residents of certain areas based on race or ethnicity. It created maps that reinforced systematic denial of mortgages, insurance, loans, and other financial services based on location (and that area’s default history) rather than on an individual’s qualifications and creditworthiness. Notably, the policy of redlining is felt the most by residents of minority neighborhoods.

Redlining

This definition of redlining is from Investopedia.com with the emphasis on the last line added. In America’s recent history, redlining is one of the most galling and visceral examples of systemic prejudice. It showed up on literal maps in which the desirability — and long-term prosperity — of various neighborhoods were color-coded according to how “hazardous” they were deemed to be.

The single factor that made a neighborhood hazardous? The percentage of Black families in its population (with the presence of first-generation immigrants being only slightly better according to this spectrum of hazard.)

Most American cities of any size have a map where some neighborhoods are clearly shown to be unworthy of lending and other kinds of investment. In aggregate, they form a shameful cartography of racism and an easily navigable travelogue of disinvestment. The maps themselves were created by federal bureaucrats in the post-war era as a response to the advent of the 30-year mortgage. This brought the dream of home ownership within reach for a generation of Americans… but not all of them.

Buncombe County, NC & Reparations

Officially, redlining came to an end after about 30 years with the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1968. Title VIII, commonly known as the Fair Housing Act, was meant to end discriminatory practices in housing. Fifty-two years later, the country finds itself in the midst of a continuing racial reckoning, one which reached a boiling point after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. Later that year, Buncombe County, North Carolina and the City of Asheville passed a series of resolutions calling for “reparations” as a means to address their communities’ legacies of racism and prejudice.

An analysis of property assessments and tax burdens by Urban3 shows that simply because a government has stopped actively engaging in racist practices doesn’t mean they have halted racism’s ongoing harm.

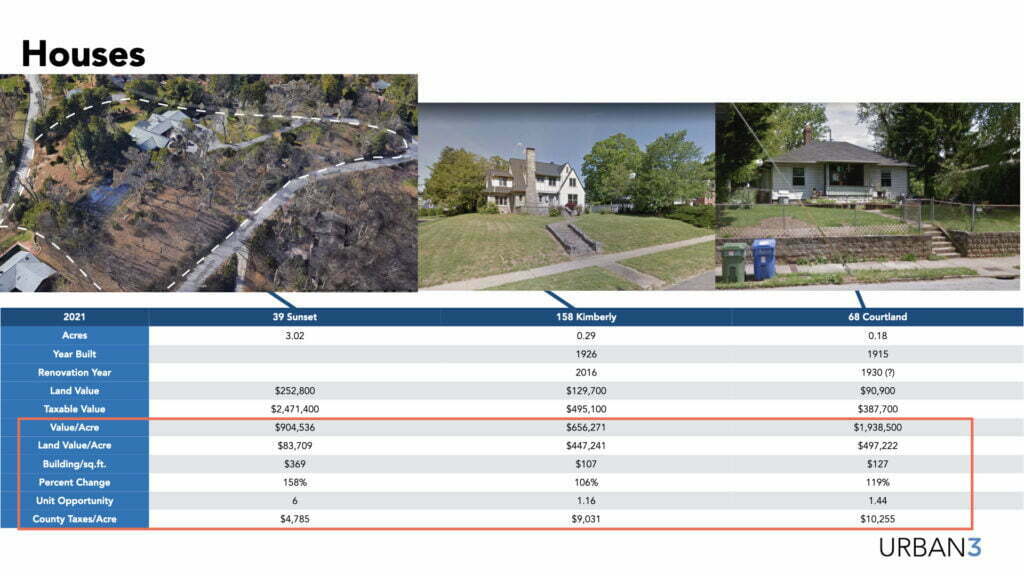

A case in point is the wildly uneven and inequitable valuations being assessed to properties in various parts of Buncombe County. Urban3 principal Joe Minicozzi led a webinar comparing three parcels in his hometown of Asheville — his Black next door neighbor’s modest bungalow, a larger home on the ninth hole of the Grove Park Country Club, and a much larger mansion (with a tennis court, natch) on mountainous Sunset Drive. After the most recent assessment, Joe’s neighbor will pay more than $10,000 in property taxes/acre on his home, valued at $388,000, compared to less than half that paid per acre by the owners of the more expensive homes in predominantly white enclaves.

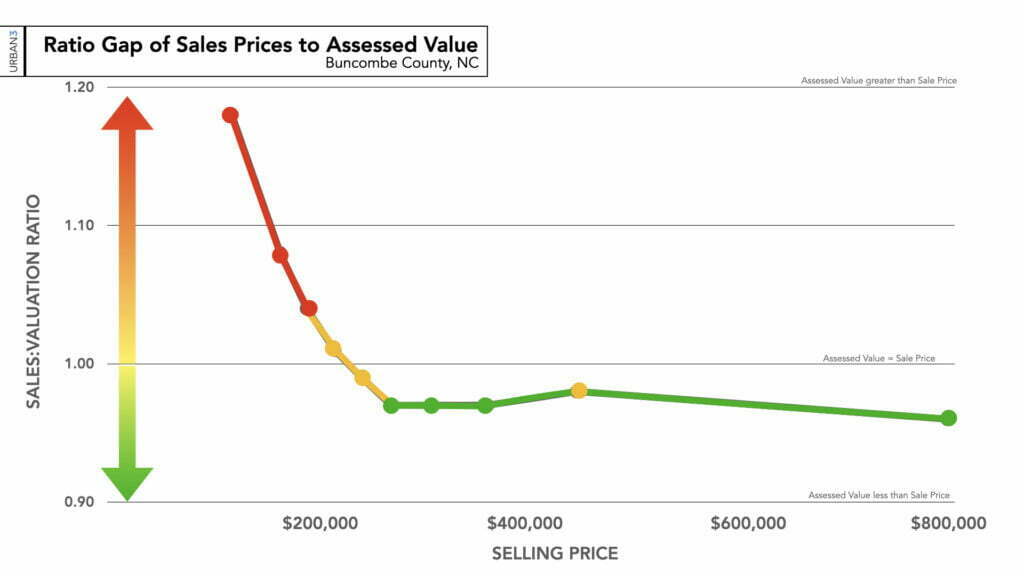

This is a problem, but it’s not a new one. Assessment cycles occur once every four years in Buncombe County. A look at the data reveals a long-standing pattern of assessments that come in higher than the purchase price for lower-valued homes, yet higher valued homes are assessed lower than their purchase price.

That means bigger property tax burdens are placed on the lowest-valued homes and the families that live in them. This is particularly troubling given that wages in the region have largely remained flat for decades.

It should come as no surprise that the vast majority of these more heavily burdened property owners are people of color, residing in neighborhoods that were redlined decades ago. The Assessor’s response, “it’s just the math, and there’s nothing we can do” is no longer acceptable. People with fewer assets are shouldering a greater share of the community’s tax burden.

Residents in cities like Asheville who are hoping to get on the path to building wealth through property ownership are finding their way blocked by a continuing mismatch between what many lower-income households can afford and the available inventory of homes. The high preponderance of non-local owners snapping up residences at all price points complicates this situation for all Ashevillians, particularly those who begin with the fewest options because of their low earnings.

Racist History & the Real Estate Market

“Local governments are playing checkers,” Joe commented on the vicious cycle of depleting assets and dwindling choices. “Meanwhile, the market is playing chess.” Many working class people can’t even get to the gaming table.

This matters to cities. Even wealthy white residents of metro areas who may feel that their status shields them from these problems end up feeling the strain, especially in the low-tax, low-services states of the American south. Municipal governments in these states often find themselves with little or no assistance from their state governments. City Hall needs every local tax dollar it can get to fund fire departments, parks, solid waste pickup, or any number of essential services. When wealthier properties aren’t adequately assessed, they won’t pay their fair share. Aside from its obviously perilous moral implications, racism is just bad fiscal sense.

Structural racism may be defined as literally building structures that advantage one race over another. Before the Civil Rights Act, that may look like the construction of separate and unequal public education, public health, and public recreation facilities for Black and white families. Today, it looks like policies that reinforce doctrine which no longer has any official standing, but which remains as inflexible and damaging as ever.

As Urban3’s Ori Baber puts it, when looking at the wildly disparate valuations of Asheville parcels that quite literally neighbor each other — but for a decades-old, officially invisible redline: “Inequity still has a geographic boundary to it.”

Can Property Reassessments Repair Inequities?

Who decides the boundaries of neighborhoods? In many cases, anonymous officials deep in bureaucracies who were only doing the job they were given. More to the point, though, how long must we live inside the boundaries others have set for us? And are we aware of the economic effects imposed by these geographies?

The individual assessors themselves aren’t even necessarily to blame. As the International Association of Assessing Officers state, assessors tend to be understaffed and underinvested. In the case of Buncombe County, each real estate assessor is responsible for an average of evaluating up to 10,000 individual parcels — a workload that encourages ‘rules of thumb’, not nuance, and certainly not urgent systemic reforms.

Urban3’s point is exactly that: this is a problem with our systems that calls for a fix to our systems. Our country may never have the political will or fiscal capacity to write a big enough check to make meaningful reparations to all Black families who have been the victims of racial prejudice in America. That doesn’t mean we have to continue inflicting unnecessary economic damage when we could change it today. Achieving racial equity now is a worthy and wise objective, from both a moral and economic perspective. The reparations resolutions that Buncombe County and Asheville officials passed are well-intentioned but ultimately hollow if the very values they castigate are reaffirmed through routine processes and policies.

As always, we must begin with the data to see what insights the math can offer. That must be followed, however, by the courage to do something different — not simply the easy choice of not doing the most obviously harmful thing.

Watch Urban3’s recent LAB video focused on the inequities in Buncombe County’s Reassessment process: